I run an insurance company, and I’m tempted to deny your claims. You see, every euro I don’t pay you, is a euro more to our profits.

It’s how insurance works, what can I say?

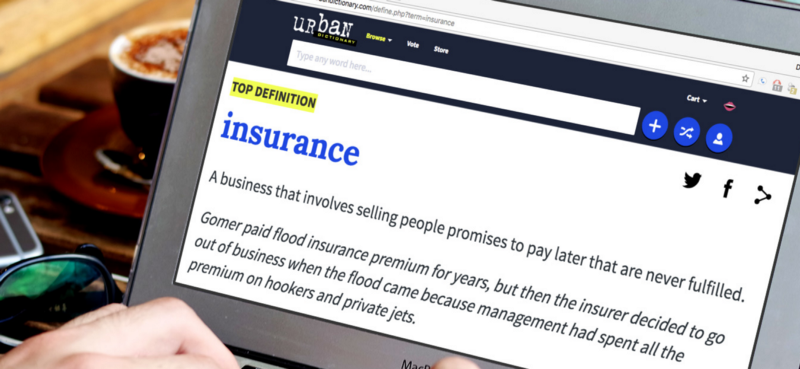

Problem is, too many media exposés have, well, exposed this (e.g. CNN), and consumers are catching on. Want to know what people think of insurance today?

Check out its definition on crowdsourced ‘Urban Dictionary:’

Ouch.

How consumers perceive insurance matters. When people think the game is fixed, they embellish claims to ‘level the playing field.’

This gives insurance companies more grounds for denying claims – sending insurance

into a tit-for-tat spiral.

Now that’s really bad.

Some studies figure this distrust costs as much as 38% of the money in the system (Wikipedia). As crazy as that euro amount may be, the true costs include other currencies too: this distrust corrodes the very fabric and experience of insurance. It’s why insurance is so unloved.

What to do?

Clearly it would be better if everyone just behaved nobly. Problem is neither side has anything to gain by unilaterally behaving better. In game theory, such gridlock is known as a ‘Nash equilibrium,’ and at the Nash equilibrium for insurance, everyone loses.

Starting from scratch

Now, imagine you wanted to break this cycle. You’re starting a new kind of insurance company, and want it to be trusting and trustworthy. What to do?

You’re sincere and well-intentioned, and you could try the ‘trust me’ approach. It’s the obvious play. But because you are sincere and well-intentioned, you shouldn’t believe your own pitch. Insurance folks aren’t bad people, and we are no more immune to conflicts of interest than they are.

Oscar Wilde said it best: “I can resist everything except temptation!”

Much as I wish it weren’t so, the problem is the system, and good intentions are no match.

This challenge haunted us in the months leading up to founding Lemonade. The more we thought about it the more we became convinced that this was a classic game theory problem.

To validate and refine our thinking we cold-called a Nobel Laureate in Game Theory. He didn’t return the first dozen calls, but ultimately agreed to help if we promised to stop badgering him. This process laid the foundations of Lemonade.

Ulysses as an integral part of Lemonade

We’ve developed some pretty cool technologies in making Lemonade. But the single most powerful tool we’re deploying is what game-theorists call a ‘Ulysses Contract.’

The legend of Ulysses tells of an island inhabited by Sirens, beautiful womanoids with beguiling voices. Sadly, they were psychopathic murderers, and sailors lured by their song met a gruesome death. Word spread, so the seamen knew what lay ahead, but each was confident he could enjoy the music without being drawn beyond the point of no return. That hubris cost them dearly.

Only one, Ulysses, cracked the code. He had himself tied to his ship’s mast so he couldn’t change course. Now that’s a structural fix.

Realizing your future-self may be unable to resist temptation, and tying your hands in anticipation, is a proven technique in game-theory to change the Nash equilibrium.

Such a Ulysses Contract underpins Lemonade.

Lemonade is a Public Benefit Corporation, a certified B-Corp, and our team genuinely wants to do the right thing. But I’d hate to test our love for social impact against our love for stock options every day.

No, if we want you to trust us we will have to do more than profess our good intentions. Much more.

We must do the only thing that truly changes anything: Tie our hands.

It’s not our money

So that’s what we’ve done. We decided we’ll take a flat fee, and if there’s money leftover we will return it to a cause of your choosing. That’s a first for insurance.

By placing ‘unclaimed money’ beyond our reach, we removed temptation, and changed the game.

That changes everything. Insurers typically make money by investing premiums (“float”) or by paying out less in claims and expenses than they took in premiums (“underwriting profit”). Lemonade relies on neither. We collect premiums monthly, so the money earns interest in your bank account, not ours, and we return unclaimed money at year’s end in Lemonade’s Giveback.

Knowing that you embellish claims at the expense of a cause you believe in, may change your behavior too, setting off a virtuous cycle. Ultimately we’re after a new Nash equilibrium, one where aligned interests breed trust, resulting in a product that is inexpensive, hassle-free and lovable.

I run an insurance company, yet I’m not tempted to deny your claims.

It’s how Lemonade works, what can I say?