“I take comics very seriously, and I was having trouble taking my mental health seriously,” says Jason Adam Katzenstein, author of the new book Everything Is An Emergency. “I made this calculation that if I made comics about my mental health, then I would take it more seriously. And weirdly, it worked.”

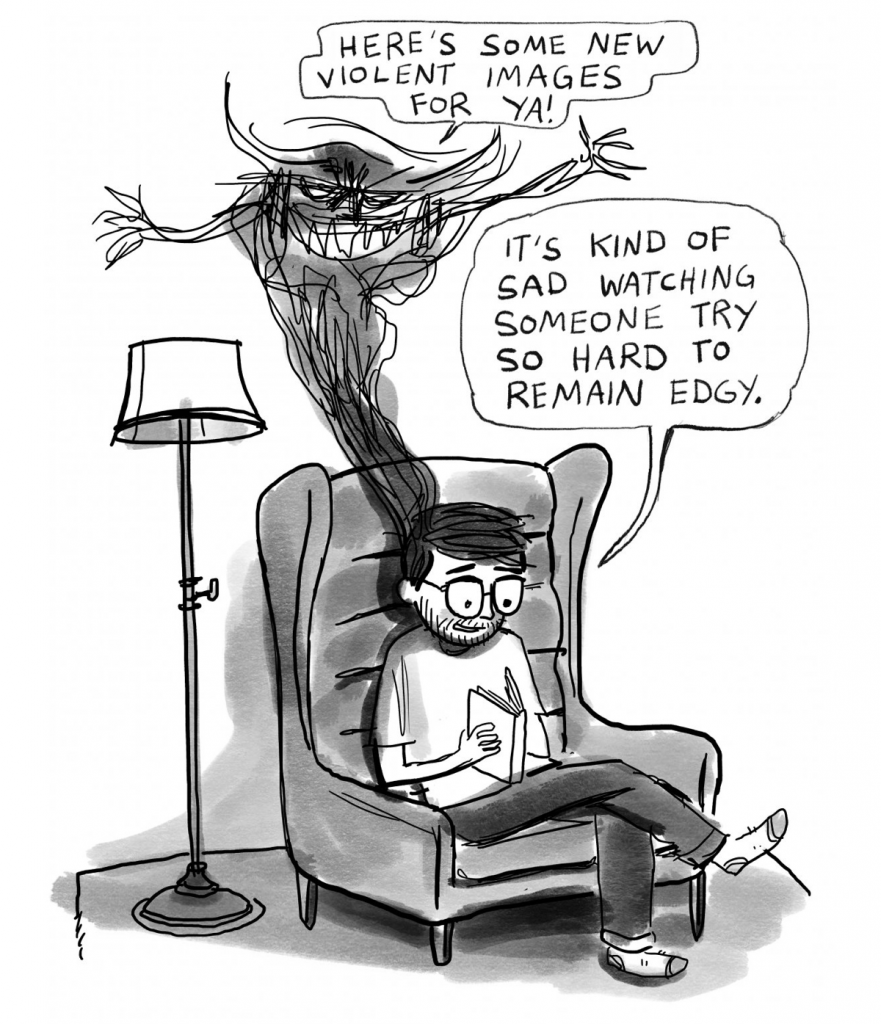

Katzenstein, a regular cartoon contributor to The New Yorker, set out to document his struggles with obsessive-compulsive disorder. While many people have a passing familiarity with OCD—and a vague idea that it involves a lot of hand-washing—the condition is often misunderstood. Katzenstein compares it to having a record player in your head, stuck on a song that you never wanted to hear in the first place.

Everything Is An Emergency proves that comics can be a powerful tool to explore things that are intense and upsetting. They allow plenty of room for self-deprecation and whimsy—even when the subject is something as heavy as mental illness. Case in point: Katzenstein’s visual pun about what it felt like to “hit rock bottom.” It shows him huddled on his bed, crying, while a goofy-faced rock shakes its butt in his face.

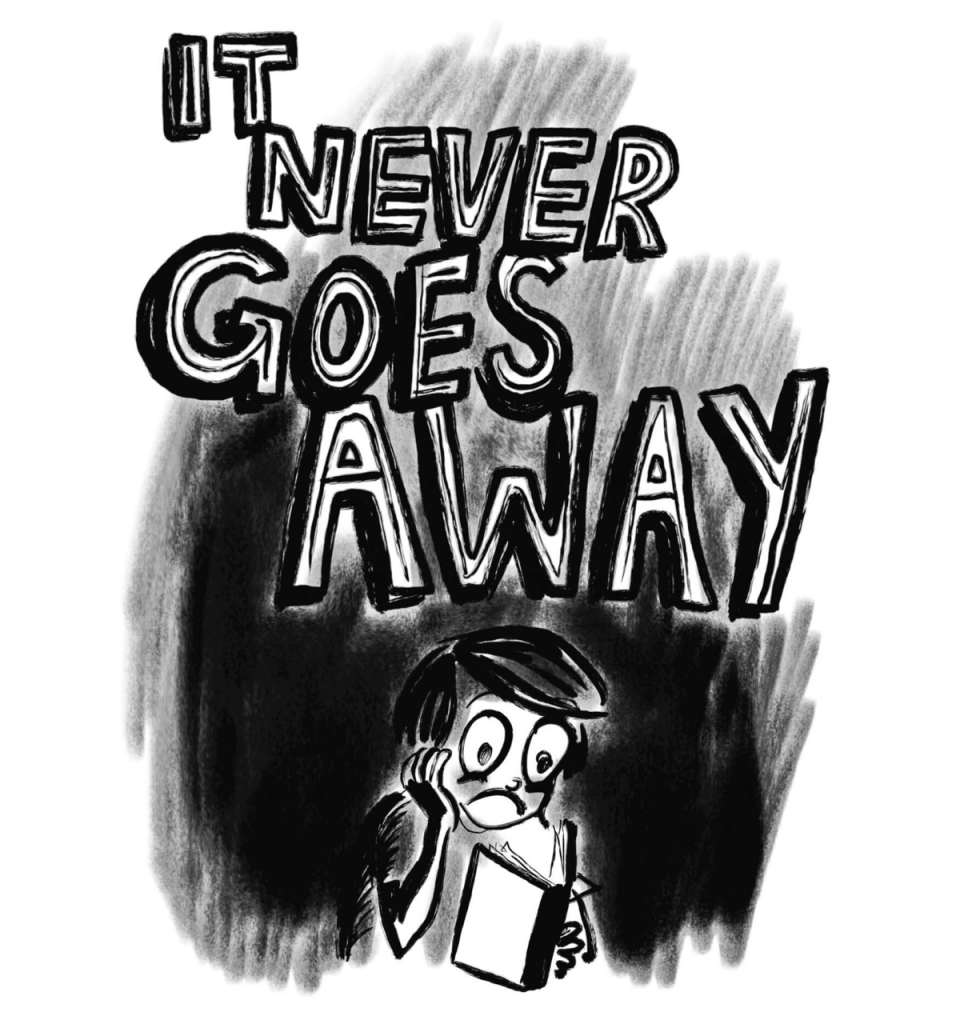

Throughout the course of the book, we watch Katzenstein’s anxious journey unfold. He has trouble driving, obsessed with the idea that he may have run over pedestrians. He fixates on germs and contamination, overanalyzes every romantic relationship he’s in, and suffers panic attacks on the subway. “For as long as I can remember,” he writes, “I’ve dreaded some abstract terror that will destroy me.”

Throughout the course of the book, we watch Katzenstein’s anxious journey unfold. He has trouble driving, obsessed with the idea that he may have run over pedestrians. He fixates on germs and contamination, overanalyzes every romantic relationship he’s in, and suffers panic attacks on the subway. “For as long as I can remember,” he writes, “I’ve dreaded some abstract terror that will destroy me.”

Spoiler alert: It’s not all doom and despair! Everything Is An Emergency points toward a healthier future, with Katzenstein slowly groping his way toward normalcy.

Drawing comics was a major component of his own redemption. He mentions Brainlock, a book that suggests OCD sufferers should purposefully expose themselves to something triggering—and then delay doing anything about it. For instance, someone with fears of contamination might force themselves to touch a dirty surface, and then wait ten minutes to wash their hands.

Those ten minutes can feel like an eternity. And so, as Katzenstein explains, it helps to “do something comfortable in that period of time, something that puts you at ease.” For him, that meant drawing comics—which ended up being about his own obsessive-compulsive thoughts. “Drawing, and comics specifically, have always felt very meditative and centering for me. It really is my comfort zone.”

These early cartoons were the seeds of Everything Is An Emergency. But it was only until Katzenstein had fully immersed himself in therapy—and started taking medication—that he was able to tackle the book-length project.

These early cartoons were the seeds of Everything Is An Emergency. But it was only until Katzenstein had fully immersed himself in therapy—and started taking medication—that he was able to tackle the book-length project.

Initially, he’d worried that meds would put out his creative fire. Katzenstein couldn’t shake the outdated cliche that suffering is what’s needed to create great art. “I sincerely believed that it was the way we mythologize it: I needed to be sad to make work, and then make work about being sad,” he says.

Instead, he found a renewed energy. Instead of submitting ten cartoons each week to The New Yorker, he would turn in twenty. Some of them addressed his own OCD—like one in which an “oven is wondering if anybody remembered to turn it off.”

“I was just feeling better,” Katzenstein says. “There was a big weight… I didn’t fully appreciate how much it was holding me back from doing the things that I love.”

And so Everything Is An Emergency is a real-time record of Katzenstein getting better, made as he was getting better. In some ways, the book “is all just an ad for Zoloft,” he jokes. He finds solace in group therapy, starts reading Jenny Odell, and gets used to a world in which his mind is no longer a broken record player.

And so Everything Is An Emergency is a real-time record of Katzenstein getting better, made as he was getting better. In some ways, the book “is all just an ad for Zoloft,” he jokes. He finds solace in group therapy, starts reading Jenny Odell, and gets used to a world in which his mind is no longer a broken record player.

Katzenstein’s book certainly isn’t the first time that comics have been used to explore mental illness. One touchstone was Allie Brosh’s 2009 graphic novel, Hyperbole And a Half. “She was really clear-eyed,” he says. “She wasn’t afraid to tell the truth about her depression, or explore the darker corners of these stories. It was that tightrope walk that she did that has always stuck with me.”

He was also moved by the essays of Fran Lebowitz. “Whenever I read them, I leave thinking: ‘She’s not okay, is she?’ But I also laugh a lot,” Katzenstein says. “I love that tension. I thought: ‘Oh, I can also do comedy about not being okay.’”

Mental illness is often discussed in hushed tones. It can be embarrassing, or at least uncomfortable, to open up about these experiences. For Katzenstein, comics were the perfect solution: a creative, occasionally silly tool to capture something that was dead serious.

“I was trying to be really true to how OCD actually feels,” he says. “Sometimes it does feel surreal or funny….One thing that I hadn’t seen much of in existing OCD literature and stories was the comedy of it all. The absurdity of it all.”