It’s a smell he’ll never forget.

An hour earlier, Jesse Morris, a managing partner at a venture capital firm, was at a meeting in downtown Manhattan, only to see he had two missed calls from his superintendent. He figured he should pick up, since his super is never one to call.

When he answered on the third try, the voice on the other line said it to him straight: “Your apartment is on fire.”

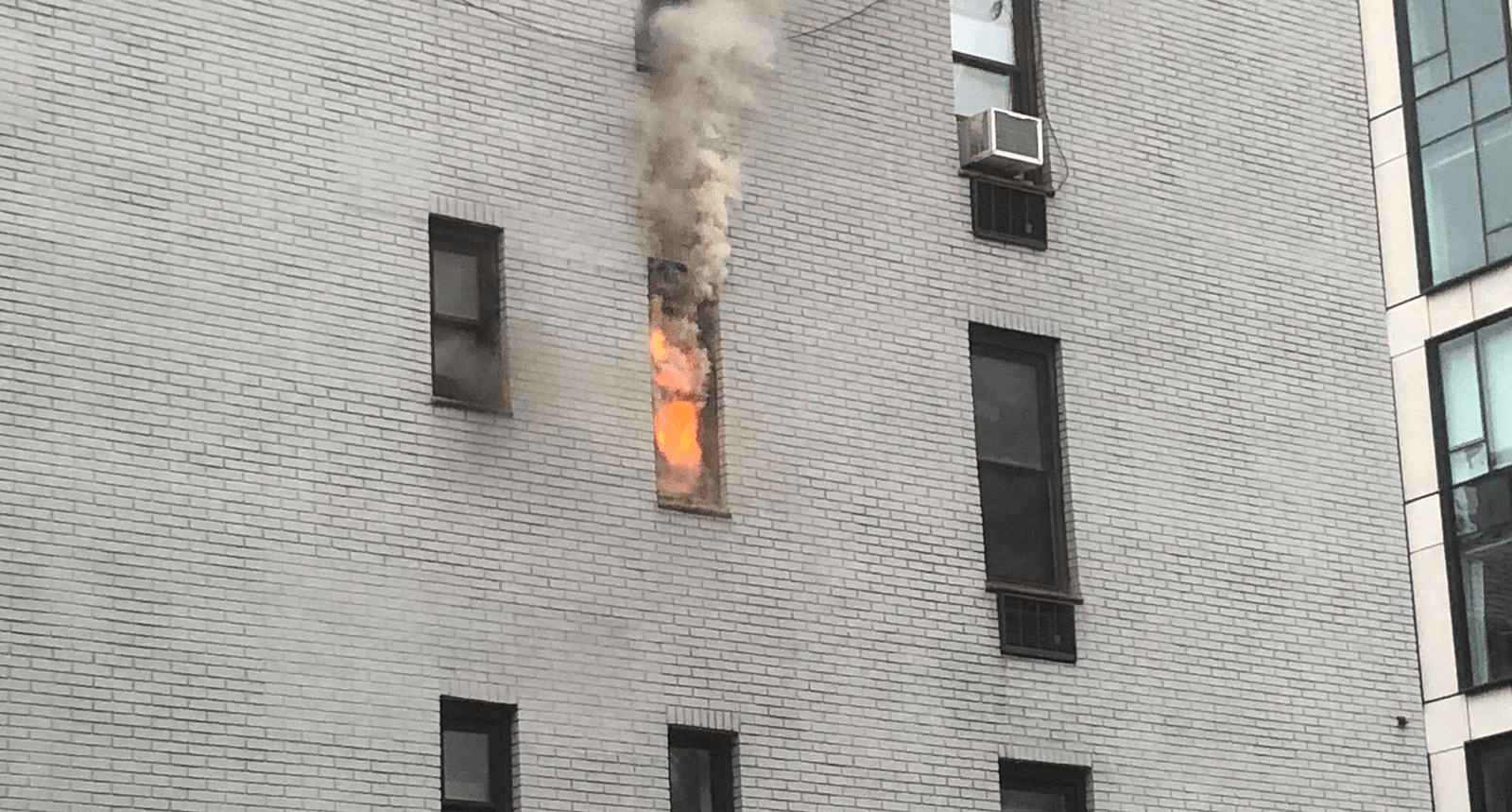

Jesse caught a cab home, 20 blocks or so from his meeting. Firetrucks and barricades were surrounding his five-story, grayish apartment building, nestled above a vegan burger shop and Thai noodle joint on the corner of Lexington Avenue.

He saw his neighborhood had gathered ‘round, and spotted his alarmed barber and laundromat owner, worry plastered over their faces.

He was numb, but in a moment of odd clarity was ready to follow instructions.

“I went into problem solving mode, and remember the incredible FDNY firefighters who told me the fire is out, and to go up and collect all – if any – remaining valuables. They handed me a garbage bag, and asked if I had insurance. I did,” said Morris.

The smell of smoke accompanied him on the walk up to his apartment; his shoes made squeaky noises as he laid foot on his sopping wet floor.

“I felt like I was in Armageddon. I scanned the apartment quickly to see if there was anything that could be salvaged,” Morris recalls. He found his social security card and passport, and shoved some smoke-ridden clothes into his garbage bag.

Standing down on the street, carrying everything he had left on his back and a garbage bag, Morris says that while he was hurting inside, he suddenly had a sense of gratitude. “It’s an odd sight to see your home completely destroyed, but I remember thinking, thank god no one was injured.”

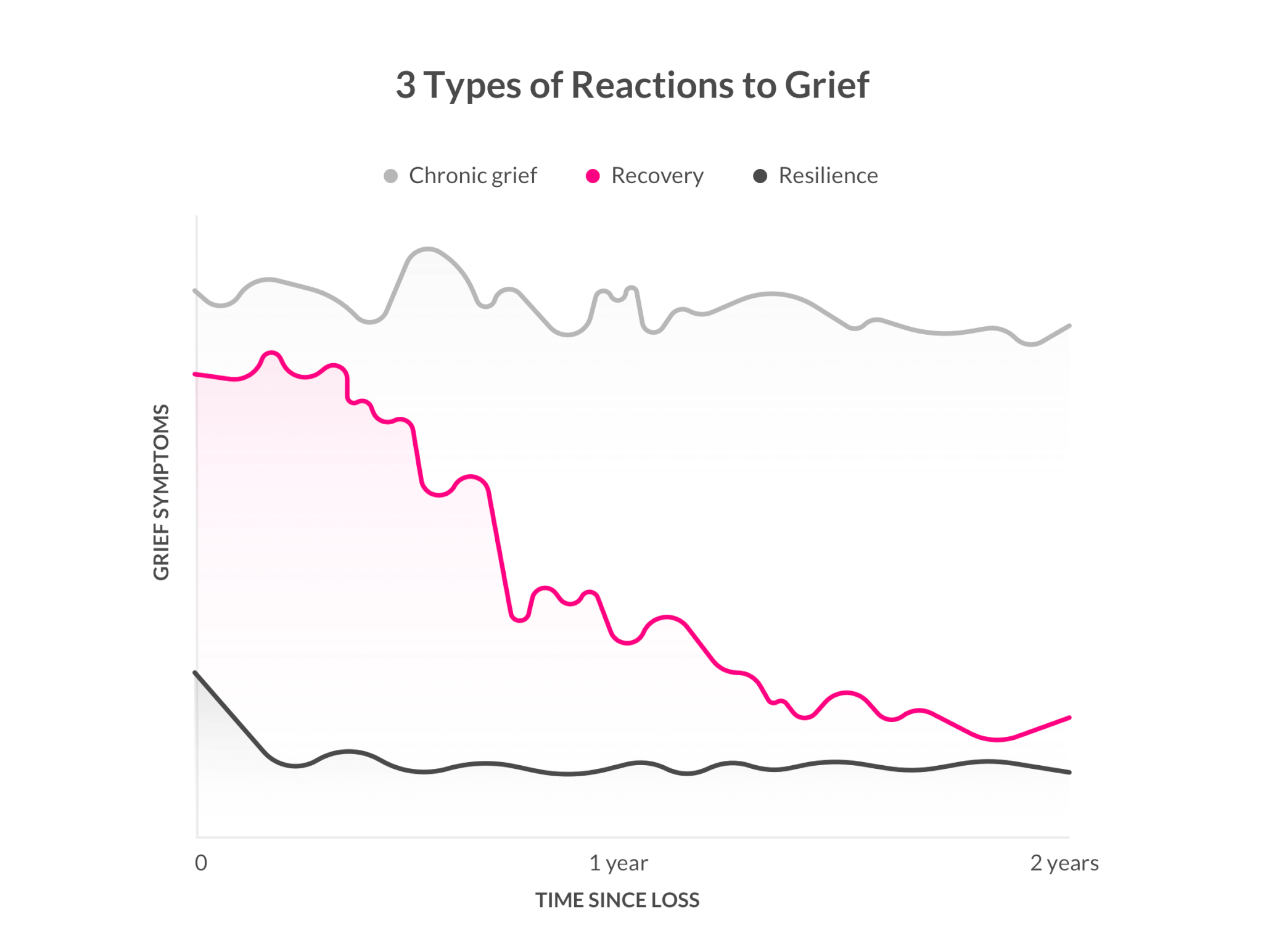

Morris’ moment of clarity, coupled with his sense of gratitude, are what psychologists call resilience: the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant sources of stress. It’s the ‘bouncing back’ to real life even though you are experiencing emotional distress.

Resilience is a driving mode these days, as wildfires rage across California and Australia. Victims of house fires often have to be quick to be resilient, while coping with long-term effects on their lifestyle and wellbeing.

The scope of resilience is wide; it emerges in all shapes and forms following adversity, and is measured by the ability to recover and live a more resilient life after overcoming a crisis.

While this includes life-threatening, traumatic, and often tragic situations such as refugees fleeing a regime or recovering from a freak accident, people can demonstrate resilience even if the adversity is considered to be on a relatively small scale.

Resilience has often been referred to as “ordinary magic;” while it seems like an extraordinary feat, it is more common than once thought – it’s a human trait inhabited by all, but only used by some.

No matter how extreme the adversity, people will bounce back to their happiness baseline in what seems like a short time, Harvard psychologist Dan Gilbert found in numerous studies. In fact, it surprises us how fast the vast majority of people who experience any kind of tragedy or trauma get back to their day-to-day routine, since, as Gilbert says “We don’t recognize that we are as resilient a species as we turn out to be.”

Gilbert dubs this our “psychological immune system.” It’s how people, mostly unknowingly, reset their brain and change their views of the world so they can feel better about their life, here and now.

But since these processes are largely unseen, humans don’t realize they’re capable of overcoming adversity – and to what extent.

Gilbert says that’s a good thing. After all, can you really prepare yourself for tragedy? Only when it hits us to do we do “the very things that evolution would have us do.”

The unbelievable heroic stories coming out of the climate crisis-induced havoc in recent years exemplify this innate human quality to deal with adversity, even if you’ve never prepared for it.

Nichole Jolly, a nurse at a hospital in Paradise, California, was racing to flee the flames in the 2018 deadly Camp Fire when she called her husband from her burning car to let him know she wasn’t going to make it out alive. He replied: ‘Don’t die, run. If you’re going to die, die fighting, you have to run,’ as she told CNN.

With ashes and smoke blinding her way, Jolly jumped out of her car, and ran. She put her hand in front of her and happened to touch the back of a firetruck. Two firemen pulled her up and covered her with blankets. She remembers thinking, ‘I’m safe, I can live in here.’

But then she overheard the fire crew call for air support, and heard them say, “we’re not going to make it.” All she thought was “I need to run, my husband told me to run!” Again, Jolly felt trapped, and thought she wouldn’t survive the harrowing situation. But then, almost “out of nowhere” a bulldozer came and paved a path forward, saving them, and took them to the hospital.

When she got back to the hospital, she went right to work, and stayed busy. “We didn’t think about ourselves and our possessions we just lost… we just helped these people, that’s what nurses do.”

Jolly’s almost immediate swing back into “what nurses do” was necessary to keep going. In his book, The Other Side of Sadness, Columbia Professor George Bonanno calls resilience an embedded human experience: “Our reactions to grief seem designed to help us accept and accommodate losses relatively quickly, so that we can continue to live productive lives.”

Morris cites a similar sentiment. While recovering from his home fire was incredibly painful, and the logistics of getting back on his feet took a few months, he says the trauma itself “weirdly made me productively deal with the situation. I purposely chose to move back into my home. I didn’t want to push it out of my life – in fact, I fell in love with my home all over again.”

He admits that the trauma also made him become a minimalist overnight: “I realized I didn’t really need anything material that was in my apartment before the fire.”

Bonanno confirms this ‘reset’ phenomenon in his research: even when it’s impossible to shut out the loss and pain, the only option left is to deal with them in the best way possible.

Perhaps one of the biggest myths of trauma and loss – and where the power of resilience is undervalued – is the fiction that the harder you try to ‘solve’ your sadness, the better off you are.

In fact, around 50-60 percent of humans who underwent trauma appear to be fine – even in the short term, Bonanno says. The myth used to be that these people are ignoring their emotions or packing them away only to ‘explode’ at a later stage; but in fact, it’s resilience that’s allowing them to get on with their lives — not denial.

Jolly’s wounds of trauma still run deep, but her resilience is evident in how she has rebuilt her life, family, and home. As she told the local North California station Action News Now, her voice quivering and her eyes teary: “Everybody lost something in this fire. It’s going to be ok. We’re going to rebuild. And I want people to be there for each other. Because that’s what made this town so great. We are such a great town. It’s not the things we lost, it’s who we are. We are a great town because of the people that we are.”