Determining the perfect gift can be quite stressful.

Should we get a lavish gift for our loved ones or not? And if we get a gift, should we spend our paycheck on material presents or on a shared experience? Should we get a large gift to prove our love?

Here are some findings from social science that we should take into account when buying gifts.

Recognize that giving makes us happier

From the perspective of rational economics, gift giving is anything but rational. After all, we never really know what the other person wants, and anything we pick out for them will typically be less suited for them as something they would pick out themselves.

This is why traditional economists view gift-giving as an irrational exchange. Some go as far as calling it ‘wealth self-destruction.’

Yet, this analysis ignores the fundamental reasons that we give gifts in the first place: to increase human connection, friendship, and reciprocity.

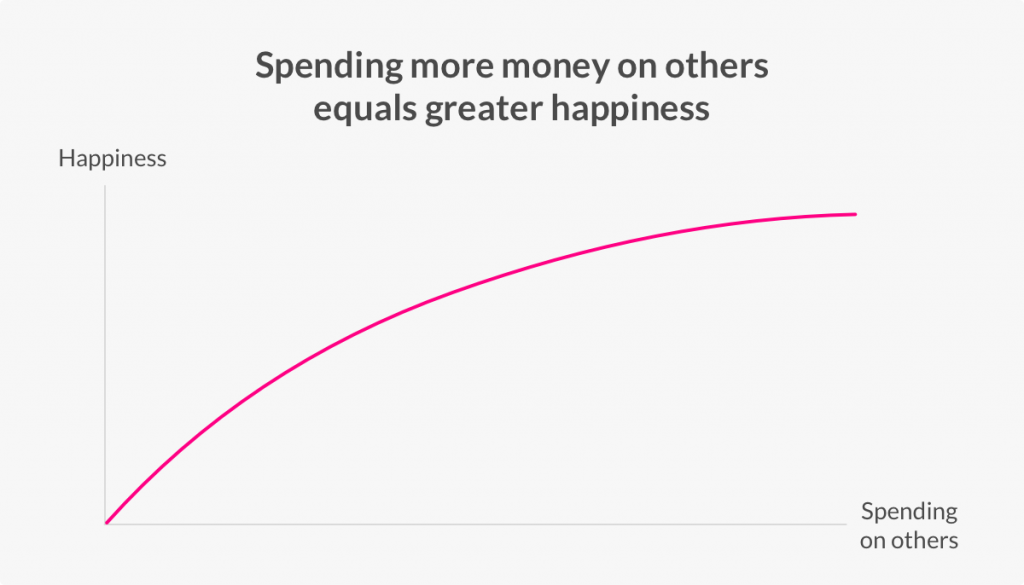

For example, a Harvard study found that people who spend more of their income on others tend to be happier. In the study, led by Prof. Elizabeth Dunn, participants who were randomly assigned to spend money on others experienced were more happy than those assigned to spend money on themselves.

Gift-giving can create happiness on both sides, and when the gift goes to a person we know and like, they can create a stronger social bond.

Long-lasting gifts will remind us about our relationship

The philosophy behind gift-giving is actually quite straightforward. We give gifts to remind the recipient about our feelings towards them, and to strengthen our social bond.

Gifts like headphones are always good because every time the recipient uses them, they’re reminded of you.

Here’s one more element to think about: give a gift that gets used intermittently. Things like a painting often just fades into the background. An electric mixer on the other hand, when used, gets noticed. Every time you use it, you’ll think of the person who got them for you.

Try to give gifts you’d feel too guilty buying for yourself

The best way to think about gifts is through the “pain of paying.” Pain of paying is the feeling you get when you really want something, but would feel too guilty buying it for yourself. This category shouldn’t exist, according to standard economic theory: if you really liked it and could afford it, you’d buy it. But a high pain of paying usually means it will be a meaningful present for someone else.

For me, fancy pens meet this description. I don’t use pens that much, but I’d be pleased to get a really nifty one. When my students defend their dissertations, I ask everyone on the Ph.D. committee to sign the required forms with an expensive pen, and then I give the pen to the student. It’s a prototypical good gift, because it’s something that they would probably feel too guilty buying for themselves, but would be pleased to receive from me. Plus, it has positive associations as a memento of the day.

This is yet another reason headphones can be a great gift. They’re a luxury: people have a hard time buying them for themselves (high pain of paying), and they get used quite frequently. Every time you put them on, you’ll think of the person that got them for you.

Put yourself in the recipient’s shoes

Often, we gift something to a friend or loved one that we would want to receive ourselves. If you want to push yourself a bit more and invest more time into the gift, try to think of what the recipient would like among the things you like. This is the challenge of empathy.

Instead of just saying, “I bought you membership to this yoga class because I love it and you should too,” first think whether yoga is something your recipient would like doing at all, and maybe if they would like doing it together.

The great challenge lies in making the leap into someone else’s mind. Psychological research affirms that we are all partial prisoners of our own preferences, and have a hard time seeing the world from a different perspective. But whether or not your partner likes yoga, it may give your partner joy that there was even thought process involved.

Take more risks

The problem with gift giving arises with people’s own risk aversion. Since most gift givers don’t really know what recipients want or need, they become deterred by the logistics (“What color should I buy? What size?), and because of that, they don’t end up taking risks. They usually wind up buying things like wine, chocolates, and flowers, which don’t give the other side much value.

It turns out that we need to take the risks – and despite the challenge of empathy, opt to give a meaningful gift that has significance.

If you give me a bottle of wine, sure, we’ll consume some wine, but it will go away. But if you take a risk and give me something I don’t like, I’ll get to learn something new. I might even learn about the stuff I don’t like, and then maybe I’ll give it away to somebody else. Whatever I do with it, it’s not necessarily going to be worse than a bottle of wine.

This concept is easier thought about in bulk: If you gave 10 presents of wine, chocolates, and flowers, the long term impact would be zero. If you give 10 presents that are ‘riskier,’ and only 8 of them hit the mark, you’ve made a much longer lasting positive impact than 10 empty gifts.

Wrapping it all up

Giving a gift does more than signify your feelings towards your recipient – it also creates a culture of reciprocity in relationships. Once you give someone a gift – whether it’s for a holiday, or just because – you set the tone for your relationship moving forward. You give to your friend, and your friend will want to give back to you.

Since studies show that gift givers are happier people, this holiday will make you and your partner happier – and not just in a small way. And when you do finally give a gift, just remember to take a risk.