By the time 8pm rolls around I don’t want anyone in my lap.

I don’t want anyone breathing in my ear, or rubbing their face against my leg. I don’t need all that neediness.

The 19-month-old human boy who shares our apartment is finally asleep, and all I really need is to briefly unplug my brain, eat some dinner, and watch HBO.

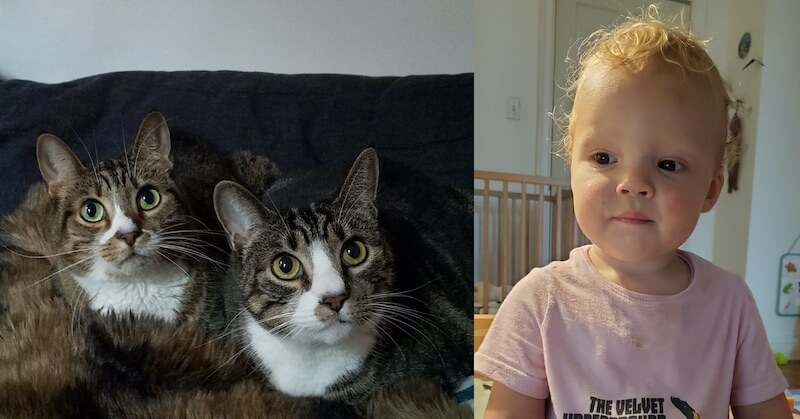

But there they are, the cats: as adorable as ever, moon-eyed and meowing, desperate for love. And here I am: tapped out for anything beyond a cursory petting. Emotionally spent. In need of some personal space, which is in direct conflict with the presence of two furry, purring, four-legged friends.

Am I a monster, or what?

Self-portrait as cat person

My cats—Uni and Chloe Zola Volcano—are a little over a decade old. They’re sisters, rescues from a Brooklyn shelter.

I didn’t grow up with cats, but I became an aficionado in my twenties and thirties. My Instagram feed in those years was 95% kitty (the answer to “how many pictures can you take of the same damn cats?” being “a lot”).

I started an “interview” series in which my cats chatted with prominent literary personalities. I marveled at how wonderfully dog-like Uni and Chloe could be: clingy rather than aloof, effusive not cold. I painted pictures of cats, was a sucker for any movie that could pull off a talking feline. I was, unabashedly, a cat person.

Sometimes this meant making pretty big sacrifices, or at least changing the way I lived. Furniture was doomed to destruction; having allergic friends over to visit was a challenge. I grew used to my clothing being composed of 45% cat hair.

Then, in early 2019, Uni was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism—cured by a treatment of radioactive iodine that required her to be quarantined in a separate room for about two weeks. I would briefly enter to feed and pet her in a lo-fi version of a hazmat suit. Oh, and the whole thing, without pet insurance for cats, cost around $4,000. But isn’t that what we do for our babies?

My wife got pregnant not long after Uni’s recovery, and the cats reacted in predictably adorable ways. Chloe was a bit more detached, but Uni proudly draped herself across my wife’s belly, as if she were helping to warm an egg.

Fast-forward to 2021, and the child has hatched. I’m struggling with this love triangle, or rectangle, or whatever: Baby, wife, cats. The baby, being a baby, is non-stop need. My wife and I try to carve out little slivers of time in which we can be functioning adults, unencumbered.

The cats, meanwhile, circle and yearn. They beg to get into the bedroom (they’ve been banned from overnights since the pregnancy). They are crazy about being close, as if they draw their energy from whatever human power source they’re able to plop on or across.

Before the baby was born, I thrilled at this feline attention. Now, it’s claustrophobic: too furry, too meow-y, too much.

And yet this is my fur fam, constant companions who’ve been with me through all the joy and struggle of the past ten years! They’ve gamely put up with all these new changes—with the small human who terrorizes them with gleeful shouts and too-hard petting—and they deserve better than what I’ve been able to give.

Baby integration for a happy catdom!

So what to do, besides just feeling crummy and insufficient? I contacted a cat therapist for some insights.

Carole Wilbourn has been a pioneer in the field since the 1970s, her practice covered by everyone from National Geographic to Vice and CNN. Her website bills her as “the first and last resort when a cat’s problem seems insurmountable.” When we connect on the phone, she sets some boundaries regarding terms: “animal companion,” rather than “pet,” “guardian” rather than “owner.”

Cat therapy admittedly seems pretty damn bougie. To be totally honest, I’m expecting some truly woo-woo advice; Uni and Chloe on a tiny couch, having their Freudian demons exorcised.

But—who knew?—the conversation is sharply informative, and makes me feel a lot less alone. Turns out I’m not the only new parent who’s been thrown off by how a baby can mess with the cat/human dynamic.

“The cats become sort of an obstruction,” Wilbourn says. “You’re thinking: ‘Oh God, I can’t do it, they’re in the way. The other part of you is: ‘Oh my God, I’m sorry…’”

And that’s it, exactly—this cycle of annoyance and guilt… of wanting my cats to continue to be cute and present, but only on my specific and unpredictable terms. That’s a pretty shitty, selfish feeling. But I spend most of the day being a Dad Dad, and often don’t have much left when it comes to being a Cat Dad.

“As we know, cats are creatures of habit,” Wilbourn tells me, “and they do not like anything new or different—unless they initiate it.”

A baby’s arrival in a feline household—or what Wilbourn refers to as a “catdom”—can be seriously stressful. It makes total sense, as she explains it: Babies are time-consuming. But the presence of a new baby might cause the cats to really need extra support, love, and attention… all when those are in very short supply. That’s a tricky combo.

“What happened to the nurturing?” Wilbourn asks, rhetorically. “Well, they’re putting food down, they’re changing the litter box, that’s not really enough. Before, the cats were there to comfort you, and you to comfort the cats: mutual comfort. And now, since you have less time to nurture yourself…. the cats are disrupted.”

Thankfully, Wilbourn has some actionable advice, which I’ll do my best to summarize here.

Talk to the cat!

Wilbourn stresses the distinction between what she calls “touch therapy” and “talk therapy.”

Now, before you run away screaming—this doesn’t mean that you have to believe that your animal companion speaks English, or even understands anything you’re saying. But “your body language and tone of voice,” Wilbourn explains, can go a long way toward making your cats feel like a valued part of the inner circle that includes your partner and your baby.

While snuggling and petting your cat is a nice way to show affection, it’s not the only way. “Touch doesn’t [always] work,” Wilbourn says. “Sometimes, you can’t even be petting two cats at the same time.”

When a baby is stealing your time and attention away from them, cats are left feeling like outsiders. “Me too, me too! This is what we have,” Wilbourn explains. “We want to chip away at the me too.”

That’s a simple fix: “When you are doing something with the baby, even if [your cats] can’t see you or even if they can’t hear you…say ‘Right, guys?’ Or you can say their names. Say as much as you want, the more the merrier—but say something.”

Like most mundane but invaluable therapeutic insights, this one feels really unnatural to put into practice at first. But after intentionally trying to increase the way I talk to Uni and Chloe, it does seem to help—or at least it makes me feel better.

It’s about seeing the cats as companions who can respond to verbal affection, rather than thinking of affection as a purely physical task: snuggling, curling up on the couch, tickling that tuft of fur beneath the chin… all that contact stuff that can be a little burdensome after a full day of holding, feeding, changing, and wrestling with a squirmy human baby.

Set pre-determined chill times

“Cats’ behavior can become deviant because they feel abandoned, they feel they’re getting less,” Wilbourn says. “You almost have to write it in: 10 o’clock, 10 minutes to spend with my cats. Just like you have a routine for the baby.” In fact, childrearing influencers like Big Little Feelings recommend a very similar tact with toddlers; they call it the “Ten Minute Miracle.”

Wilbourn knows that new parents are busy, and she stresses that there’s no harm in multitasking. “Maybe your cats likes to go in the hall [of your apartment building],” she says. You could supervise them while they wander, and read a book in the hallway while they explore, knowing you’re nearby.

If work and parenting has you completely strapped for time, you could also consider outsourcing the hang-out. “If there’s a child in the building who is cat-friendly—or always wanted a cat, but their parents wouldn’t let them have one—you can arrange [a play date],” she says.

Give the cats agency…

As you’re focused on talking to your cats more—letting them know they’re part of the club—it can also help to stress that they’re also decision-makers.

This might not be strictly true, of course, but… a tiny white lie never hurt any cat.

When I mentioned to Wilbourn how disappointed my cats seem to be barred from sleeping in our bed, after years of doing so, she suggested putting a different spin on the situation.

Rather than it being about “no cats in the bedroom, humans only,” I could sell Uni and Chloe on the benefits of not having to sleep with us. “Say, ‘we truly miss you guys—we realize you needed your own nocturnal space’…as if it was their idea.”

Likewise, she tells me that the baby itself can be presented as a decision that the cats were actively involved in.

Wilbourn clarifies that this is a bit tongue-in-cheek, but still effective (and probably not far off from how parents would acclimate an older sibling to the presence of their new brother or sister).

“Say, ‘you guys did such a good job of picking out this baby!’,” she suggests. “You want to put them in control. If they picked the baby, and they picked a good one, and had you bring it in—then it’s okay.”

Practice gratitude

You don’t have to commit to playing laser tag with your cat for three hours a day. You don’t have to feel inferior or awful for lacking the emotional bandwidth for kitten-snuggling after a long day of baby-wrangling.

But simply including your cats in the day’s conversations, and making them feel valued, can go a long way.

My cats used to be the whiskery target of my adoration. Once I entered a serious relationship, that focus shifted (if it hadn’t, I’d probably need a different form of therapy). After my son was born, though, it was so easy to see the cats as an “obstruction,” as Wilbourn puts it.

After speaking to this expert cat therapist, I realize that there’s a way forward within this new normal. Maybe I’m not a soulless sociopath for occasionally getting annoyed by a clingy kitty. And maybe the bar doesn’t have to be so high—maybe it could start with a chipper ‘good morning,’ an extra head scratch on the way out the door, a spoken affirmation of how lovely and lovable the cats are.

“Acknowledgement is so important,” Wilbourn tells me. “Everybody wants to be acknowledged. Your cats were thoroughly acknowledged until the baby came along.”

So Uni and Chloe, if you’re reading? This one’s for you.